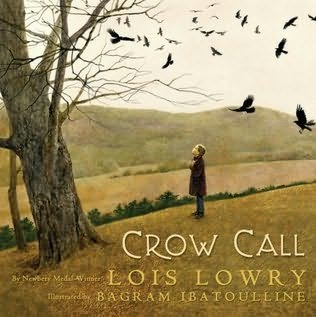

Written by Lois Lowry

Illustrated by Bagram Ibatoulline

I was fortunate to have stumbled upon Lois Lowry’s, Crow Call, as I was looking through the picture book section for another book written by an “L” author. I did not realize Lowry had ever written a picture book—and realized later through her website that this was her first. I was immediately drawn to the book because there was something about the title and the illustrations on the front and back cover that reminded me of one of my favorite picture books, Owl Moon, written by Jane Yolen.

Through the story of Crow Call, Lowry retells a true story from a childhood—an early morning when she went crow calling with her father in 1945 after his return from World War II. Early on, we realize that the young girl is rebuilding her relationship with her father and hardly feels like she knows him anymore. She says, “I practice his name to myself, whispering it under my breath. Daddy. Daddy. Saying it feels new. The war has lasted so long. He has been gone so long.” Later, the father asks, “What’s your favorite thing to eat in the whole world?” The young girl responds, ““Cherry pie.” I admit. If he hadn’t been away for so long, he would have known.”

As the story continues, the young girl Liz becomes more and more comfortable with her father. Similar to Owl Moon, Crow Call shows the powerful relationship between father and daughter and the importance of bonding. The story is told through the perspective of the young girl, and Lowry incorporates a lot of dialogue between the young girl and her father in addition to the young girl’s innermost thoughts. For example, a conversation about war: ““Daddy,” I ask shyly, “were you scared in the war?” He looks ahead, up the hill, and after a moment he says, “Yes. I was scared.” “Of what?” “Lots of things. Of being alone. Of being hurt. Of hurting someone else.” “Are you still?” “He glances down. “I don’t think so. Those kinds of scares go away.”” What a powerful conversation for the two of them to be having—it provides a chance for Liz to get to know her father on a deeper level—and a chance to understand an aspect of war.

Lowry writes using poetic and descriptive language. For example, “I try not to laugh, wanting to do rabbits next, but I can’t keep from it. He looks so funny, with his neck pulled away from his shirt collar and a condescending, poised, giraffe look on his face.” We can visualize this special moment where Liz’s father is being silly making a giraffe call and we feel the warmth of the relationship between the father and daughter. Also, “I want to scamper ahead of him like a puppy, kicking the dead leaves and reaching the unknown places first, but there is an uneasy feeling along the edge of my back at the thought of walking in front of someone who is a hunter.” We can now sense Liz’s uneasiness as she relates to her father being a hunter in the war.

As Liz and her father approach the woods, Ibatoulline creates tension through his full-bleed, double-paged spread illustrations. The full-bleed illustrations keep us at a close-distance. Just like in Owl Moon, we feel like we are intruding on this very special moment between a father and the daughter. The perspective of the illustrations does change throughout the book. At times, we are close enough to hear the conversations of the characters. At other times, we are watching from as if we are an animal peeking from their burrow.

The colors throughout the story make readers think of fall—shades of brown, black, and light blue saturate each page. The trees are bare in the woods, reminding us that winter is on its way. The trees mostly consist of diagonal lines—again creating tension and evoking emotion in the reader. The representational style of the illustrations reminds us that this story is real as we can sense the subtleties in the expressions of the characters and understand their feelings.

Although this story is nostalgic of an event in Lowry’s childhood, I feel it is relatable to anyone—young or old. Children today are still faced with losing their fathers to war. Many fathers do come back, but the bond between father and daughter must be recreated in order to make up for the time that has been lost. Lowry’s Crow Call reminds us all what it is like to get to know a loved one for what seems like the first time.